Mental Game of Poker Excerpt 5 – Inchworm

This is the fifth excerpt from The Mental Game of Poker written by Jared Tendler & Barry Carter. The book is now available from Amazon.co.uk.

“Inchworm” is a concept with a strange name that helps make the process of improving over time easier to understand. Inchworm isn’t a revolutionary new idea; it’s just an observation of how you improve over time and something you likely never thought about previously. Understanding this concept more clearly will help you to:

- Become more efficient in your approach to improving.

- Make consistent improvement while avoiding common pitfalls.

- Avoid fighting a reality you can’t change.

- Know where a skill is in the learning process.

- Handle the natural ups and downs of learning better.

There will be times when it feels like you have taken a huge step backward,

not progressed at all, or have fallen back into old habits.

The next time this happens, come back to this section.

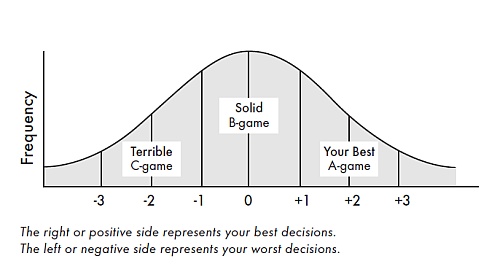

Understanding the concept of inchworm starts by looking more closely at the natural range that exists in the quality of your poker or mental game. Think for a moment about the quality of your poker decisions when playing your absolute best and when playing at your worst. In other words, how good does it get when you’re playing great, and how bad does it get when you’re playing badly?

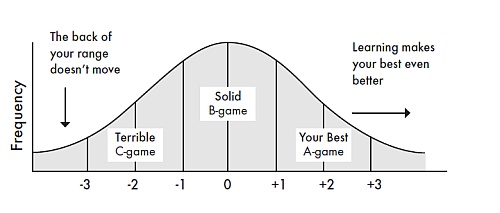

To illustrate a point, let’s say you rated the quality of every decision you made at the poker table (your best, worst, and everything between) over the last 6 to 12 months on a scale of 1 (worst) to 100 (best) and plotted them on a graph. What you’d see on that graph is a bell curve.

This bell curve shows the natural range that exists in your game and the game of every poker player on the planet—even shortstackers (although theirs is the narrowest). As long as you’re playing poker, you’ll always have aspects of your game that represent the peak of your ability, and the flip side, your worst. Always. Perfect poker isn’t possible over a large number of hands. There are times you play perfectly and other times that you don’t. Poker is a dynamic game that’s becoming more competitive. This means that the definition of perfection, even just solid play, is a moving target. As long as your game evolves, that means you’re learning. If you’re learning, that means there’s range in the quality of your decision making.

Poker isn’t the only instance where range exists. It’s everywhere you look, especially in professional sports. Take any player in a major professional sport and evaluate the quality of their skill set over a large enough sample and you’ll see a bell curve. Baseball players hit home runs and make diving catches, as well as strike out and make errors; quarterbacks throw perfect forty-yard passes into tight coverage and then throw terrible interceptions; soccer players make incredible passes setting up an incredible goal and also whiff or shank the ball.

When looking more closely at your game, for better or worse, it’s important to be honest about the reality of the range that exists. Not what you wish the reality to be, but what it actually is. Take a look at the strengths in your decision making, represented by the right side of your bell curve. These are decisions that happen when your thinking is perfect, so they come easily because you have a solid understanding of your opponents and you’re in the flow of the game. Generally, you have a great mindset and are in the zone.

The right side also includes new information gained from your own insights, training videos, talking with other players, etc., which allows you to make even better decisions than usual. Remember, these are skills at the level of Consciously Competence and cannot yet be counted as a solid part of your game.

On the other side of the bell curve are all of the terrible decisions you make. These are all the mistakes you know you shouldn’t be making, but still do. Often these are directly connected to mental game problems, such as your mind going blank in a huge pot and you fold the obvious best hand; you misread an opponent because you’re bored and your terrible bluff gets called; or you’re on tilt and play too many hands way too aggressively. Clearly, these are all the things you want out of your game because they not only cost a lot of money, but they create more frustration, confusion, and confidence problems. This book is designed to help you improve the back end of your mental game range, which means that not only will these obvious poker mistakes go away, you’ll also play closer to your mental peak more frequently.

The concept of inchworm comes in when you look at how the range in your poker game or mental game improves over time. A bell curve is a snapshot of a given sample, while improvement is the movement of a bell curve over time; something an actual inchworm illustrates perfectly in the way it moves.

If you’ve never seen the way an inchworm moves, it starts by stretching its body straight, anchors the front “foot,” then lifts up from the back end, bends at the middle to bring the two ends closer together, anchors the back foot, and then stretches its body straight again.

When you reach a new peak in your ability, the front end of your range takes a step forward. Your best just became better and that also means that your range has widened because the worst part of your game hasn’t moved yet. The most efficient way to move forward again is to turn your focus to the back end of your range and make improvements to your greatest weaknesses. By eliminating what is currently the worst part of your game, your bell curve takes a step forward from the back end, and now it’s easier to take another step forward from the front.

An inchworm illustrates that consistent improvement happens by taking one step forward from the front of your bell curve followed by another step forward from the back. The implications of this concept are that:

- Improvement happens from two sides: improving weakness and improving upon your best.

- Playing your best is a moving target because it’s always relative to the current range in your game.

- You create the potential for an even greater A-game when you eliminate your mental and poker C-games because mental space is freed up to learn new things. (Yes, the quality of your mental peak or zone can actually improve as well.)

Client’s Story

Niman “Samoleus” Kenkre

$5/$10 to $25/$50 NLHE

Bluefire Poker Coach

“It’s kind of unusual; I actually started talking with Jared when I was on a real tear, and at the top of my game. I’d been a successful pro for more than five years, but had a really rough patch at the end of 2009; I was playing really poorly and was screwed up a bit mentally. I sorted my game out on my own and went to Jared when I was playing well, because I thought in a better state of mind I would get more out of it. Plus, I figured working with him might prevent my game from slipping again.

I was really skeptical working with a mental game coach; what was he going to tell me that I hadn’t heard before? I expected goofy stuff like ‘stay calm,’ ‘don’t worry about results,’ ‘visualize yourself winning,’ blah, blah, blah—stuff you read in forums. I was really surprised; Jared has a fantastic system of learning and it had a really immediate and emphatic effect on me.

He talked about concepts, such as inchworm, in a context that I never thought about. Realizing how the front end fits with my back end was eye-opening. I always thought of my A-game and my F-game as two separate things. Jared helped me understand how they worked together, which made it very systematic and clear how to improve myself overall as a player. I now understand that when I am playing my worst game, I have to work hard to make it a little better, so it won’t be as bad tomorrow.

I also didn’t understand how emotions were part of the learning model. Surprisingly, just knowing more about that completely removed the effect negative emotions had on my play. Previously, I would take bad beats and have bad players get rewarded, and I’d react like a caveman – ‘that guy was stealing my money!!!’ I didn’t have a framework to understand those emotions, and then everything would go haywire. The whole concept of the Unconscious Competence helped to totally change all that, as well as how I went about working on my game.

Unconscious Competence may be the single most important thing Jared taught me. When I was on tilt, one of my leaks would be that I would get frustrated when players 3-bet me in position with hands they should not be playing. I would overplay my hands, and get really tilted at how they were playing. It was my weakest area, and I knew I wasn’t playing well, but couldn’t wrap my head around it. Jared laughed and told me ‘So your opponents are not allowed to play in a way that puts you at your weakest?’ Seeing it in that context made me realize instantly that my emotional reaction was trying to protect my greatest weakness. I fixed the leak, and now when I encounter those situations my head is much better. It’s still frustrating, but my play doesn’t go haywire, because playing well in that situation is now learned to the level of Unconscious Competence.

Now, every day that I play, I think of my play in the context of the learning model. My tilt-induced emotions come up far less frequently, and when they do come up they don’t affect my play as much as they used to. That’s another important thing I took away from Jared. After a couple sessions, I assumed I was supposed to have this Zen-like state of mind and shouldn’t get tilted by bad beats because I now ‘understood.’ Emotions are going to be there and just knowing that makes them easier to handle. I’ve been a pro poker player now for five years, and there has been no greater positive influence on my game than my lessons with Jared, and nothing else even comes close.”

Two Common Learning Mistakes

To further understand how inchworm applies specifically to poker, here are two common mistakes players often make, along with a solution for each.

Ignoring weaknesses. When players constantly learn new things while avoiding, ignoring, blocking out, or protecting weaknesses, their bell curve gets flatter and flatter. Weaknesses haven’t improved so the back end doesn’t move. They also have a bunch of new skills to use, so when they’re at their best, they’re better than ever. The problem is that by exclusively learning new things, they create a wide range in their game, which means that it takes a lot of mental effort to think through all these new concepts.

If you aren’t mentally sharp, there’s a dramatic drop-off in your play. So when you’re at your best, you’re better than ever; but when your play goes bad, it gets really bad.

Here are a few other consequences for this approach to learning:

- Playing your best takes a lot of energy so it doesn’t happen that often.

- Mistakes show up completely out of nowhere and are really basic.

- It feels as if you’ve stopped improving and your game has plateaued.

- You have a lot to think about and often get confused or miss important details of a hand.

To make matters worse, all the new information you’ve acquired is in the process of being learned, so it won’t show up when you go on tilt, lose focus, get tired, or are nervous in a huge pot. When any of those mental game problems happen, it feels as if you’ve just had the carpet yanked out from under you, and now you’re lying on the floor (the back side of your bell curve) with your confidence shattered, wondering what the hell happened. For some players, this leads them to question everything in their game, which furthers the free-fall like an airplane in a death spiral.

The consequence of not working on your weaknesses and exclusively learning new things could be the difference between being a slight loser and a solid winner. Preventing this from happening is actually quite simple: You must stay focused on learning the correction to your weaknesses until it is trained to the level of Unconscious Competence—especially after your A-game improves. Doing so keeps you humble, reminds you of your weaknesses, and is the most efficient way for your best to improve.

Comparing your worst to your best. Inchworm also has another important lesson that comes in handy when your game is under pressure from being on a bad run, on tilt, or having poor motivation and focus. During these times, it’s especially hard to maintain proper perspective, especially for improvement in your poker and mental game. While actually recognizing improvement may not seem like much, it can be critical to helping turn things around.

The only way that you can prove the back end of your game has taken a step forward is by analyzing your game at its worst, and comparing it with your worst during a previous tough stretch. So, rather than comparing your game at its worst to your recent peak, which can seem miles away and makes you feel worse, instead compare apples to apples, or your worst to your previous worst. Remember, it’s under intense pressure that you rely heavily on skills at the level of Unconscious Competence; so for better or worse, what shows up at that point gives you a perfect view of the greatest weaknesses in your game.

Comparing your worst to your previous worst allows you to prove that the back end of your range has improved. For example, you might not be completely tilt-free; but compared to before you are more aware of your tilt pattern, manage your tilt better so you play better longer, and quit sooner when it’s no longer possible to recover a solid thought process. Basically, you’re looking to see your worst improve; and seeing that you have improved in the midst of a tough stretch can give you a much-needed confidence boost.

The book is now available from Amazon.co.uk.